LCRA responds to flood management critics

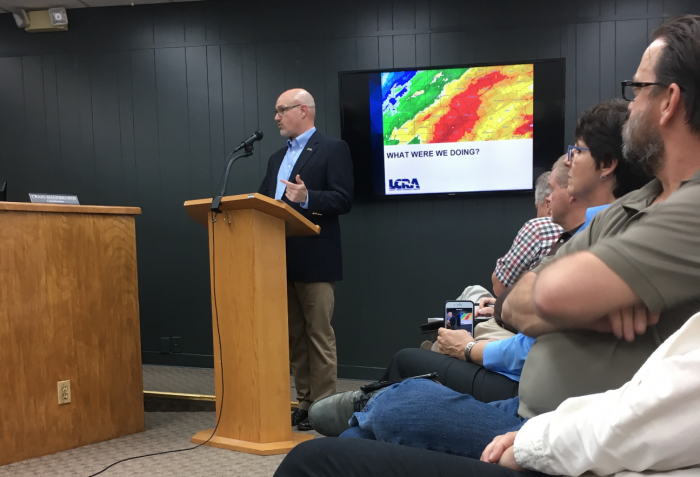

Connie Swinney/The Highlander

LCRA Executive Vice President for Water John Hofmann addressed questions from Marble Falls City Council members Feb. 5 about the entity's response to the October flood event.

By Connie Swinney

Staff Writer

A representative from the Lower Colorado River Authority unveiled Feb. 5 how the entity responded to the October flood event and addressed criticism about river management as Lake Marble Falls and LBJ residents continue to recover from the devastation.

John Hofmann, LCRA’s executive vice president for water, attended the Marble Falls City Council meeting to offer insight and answer questions about steps taken prior to and in the aftermath of the historic Oct. 16 flood.

Floodwater from the Llano River rushed into the Highland Lakes, submerging lakeside homes, prompting temporary evacuations, destroying infrastructure and private property and depositing tons of sand and debris in lakes LBJ and Marble Falls.

The flood event was described as the largest caused by the Llano River since 1935.

“Life on the Colorado River is unpredictable and at times dangerous, and during our history, the river has routinely jumped its banks and taken out everything in its path,” he said. “Regular flooding is a way of life.”

He explained that recorded history, topography and heavy rainfall combined forces to create the “flash flood alley” moniker bestowed on the region based on the behavior of the waterway.

“Our droughts aren't broken gently. They're broken with flood events,” he said. “That momentum (of ‘cascading’ topography) can also make it more dangerous during flood events.”

From Lake Buchanan to downstream of Tom Miller Dam in Austin, land elevation drops 600 feet in 116 river miles (5 feet per mile).

Along the Colorado River, the Highland Lakes is comprised six dams – creating six bodies of waters – which include Lakes LBJ, Inks Lake, Lake Marble Falls and Lake Austin, which are dubbed “pass-through” lakes, built primarily to provide hydro-electric power.

The entity utilizes the power of in-flows to harness the energy resource.

“Water gains momentum as it moves down hill, and it makes this area an ideal location for generating hydro-electric power,” Hofmann said.

“They are not designed for flood storage,” he said referring to the pass-through lakes. “They don't have any water supply component associated with them.

“Lakes Buchanan and Travis are built for (power-generating) water supply purposes,” he added.

Communities which have domestic water supply systems on the pass-through lakes, which were damaged during the October flood, included Marble Falls, Granite Shoals, Horseshoe Bay and Kingsland.

Marble Falls Councilman Dee Haddock questioned whether floodgate operations sufficiently protected property and infrastructure in the community.

“Did you open the floodgates soon enough? Did you open enough gates to allow that to get out?” he said. “If you know the water is coming, why not open the gates sooner?”

Hofmann defended the role of the LCRA staff in handling the rush of water.

“Our team worked really hard to be able to stay on top of the flood event,” he said.

“Some floods can be managed with finesse. This was not a finesse flood,” he said. “No amount of flood management can stop a river from flooding.”

A history of flooding on the Colorado River provided more insight on the behavior of the river and the Highland Lakes, created by a system of dams in the 1950s.

From the mid 1960s and mid 1980s to the 1992 historic flood and the devastating event of 1957, all were preceded by drought.

During the 1935 event, the flood flow measured 381,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) or “five times the rate of flow of Niagara Falls.”

During the October event, the flood flow measured 386,000 cfs or “just under four Niagara Falls.”

“It's the most significant flood we've had since the dams were built,” Hofmann said.

He explained how heavy runoff from several inches of rain in Junction and a saturated ground on Oct. 8 set the stage for the more severe runoff a week later, in which in-flows would increase by nearly 100,000 cfs in an hour or enough water that would fill and emptied Lake Travis.

“From no flow to Niagara Falls in an hour and a half,” he said. “It really set the stage for what happened a week later.”

In the aftermath, communities continue repairs and lakeside maintenance projects during an LCRA-extended 11-week drawdown through March 18 for Lake Marble Falls; through Feb. 24 for Lake LBJ.

Marble Falls City Councilman David Rhodes asked whether removing the excess sand deposits through dredging during the drawdown would benefit the waterway.

“It's no secret that Lake Marble Falls on the river is a choke point,” Rhodes said.

“It has happened multiple times in the last 10 to 15 years in different degrees. We get more and more sand, fill. It stands to reason, that we have less capacity to absorb these type of events. The river fills up.

“Who's responsibility is it to get that out of there, if it helps make a difference?” Rhodes added.

Hofmann said residents should understand that each flood event will change the waterways.

“Nature in this flood has fundamentally altered the look, the feel and the topography of the Colorado River on the Highland Lakes,” Hofmann said.

Rhodes also inquired about the potential impact on recreation.

“From an economic standpoint, the lake is becoming less and less navigable on the upper end,” Rhodes said. “It's moving its way down.”

Hofmann said those who chose to recreate on the waterway do so at their “own risk.”

“No water body is without risk. You have to assess the specific situation you're in and the site specific situations that you are in, and your own risk tolerance and use common sense and good judgment to make good decisions for your family.”

Hofmann explained LCRA’s role in river management, which involves generating power and maintaining the dams as well as managing the waterway from San Saba to the Gulf of Mexico.

“The issue we've heard the most about is debris. The LCRA is not going to be removing debris from the Colorado River,” Hofmann said. “This responsibility is delegated to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality,” as regulated in the Texas Water Code.

“We are going to support and have been in communication with TCEQ in their attempts to try to get money for this endeavor,” he said.

During the presentation, Hofmann recounted how the LCRA responded to the flood which included:

• Managing floodgate operations and alerting the public;

• Closing the lakes to recreational traffic for safety and property retrieval;

• Posting public safety rangers to discourage looting;

• Marking 200 navigational hazards due to debris and sand deposits;

• Assisting in dislodging boats; and

• Earmarking $100,000 to Burnet and Llano counties to assist in flood recovery.

The entity also approved an 11-week drawdown to help with cleanup, maintenance, repairs and debris removal.

Hofmann emphasized that maintenance takes priority in past, present and future projects.

The entity has spent $86 million dollars since 2010 on infrastructure on the dams and has earmarked $73 million more in the next five years.

“We will be doing some level of projects on those dams to make sure those dams can perform under the types of stresses you saw in this last event we had,” he said.

“Is there going to be another drought? Yes. Is there going to be another flood? Yes. Another significant flood? Yes. We don't know when.”

To sign up for floodgate operation alerts and river updates, go to lcra.org.

Find this story and more in The Highlander, the newspaper of record for the Highland Lakes. To offer a news tip, email connie@highlandernews.com.